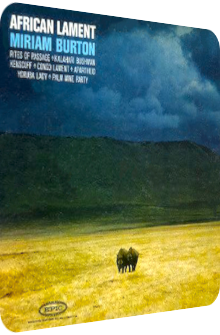

Miriam Burton

African Lament

1961

If there is lament to be found in Exotica songs and compositions, it is usually about a lost island, the return to one’s dull home or the concept of pesky critters and insects (Tsetse Fly anyone?), and even then the sorrowful state of affairs is not heartbreaking but awash with nostalgia and melancholia, both of which are not exactly abhorrently petrifying moods. So what to make of vocalist Miriam Burton’s once-in-a-lifetime Exotica stop called African Lament, released in 1961 on the Epic label? This depends more than ever on the respective listener, but more about this notion in a moment. Miriam Burton’s career circled around the periphery of Exotica at best, but she never belonged to the very core of it. Having appeared as a background singer for the likes of Harold Arlen and Harry Belafonte, Miss Burton’s vocal range is not entirely breathtaking, but remarkable enough to put her into the limelight for the first time on this dualistic album.

Comprising of seven unique compositions, one of them a three-part suite, this album only resembles symphonic attitudes but is actually realized and envisioned with a couple of session musicians. A quintet or sextet sound is in the air, brought to life by marimbas, cavalcades of drums, warbled flutes and the occasional surprise texture-wise. In the epicenter of it all: Miriam Burton and her wordless vocals. While the comparison with Yma Sumac is always close at hand, Burton more or less meets the timbre of Marni Nixon off Orienta (1959) and Polynesian Fantasy (1961) fame. How can this long-lost and recently digitally reissued Afro-Exotica album fare today? After all, it is almost torn apart by its diametrically opposite moods. As usual, I am going to tell you just that in the following paragraphs.

The very first notes and vocals make this a dubious artifact to review when an Exotica context is applied, but not necessarily when the good old adjacent Space-Age genre is taken into account. Whatever the premise may be, Miriam Burton greets the listener with a prelude that is completely based on a solo. Her wordless vocals are aptly harkening back to the album title and introduce the listener to a three-part suite called Rites Of Passage. With a runtime of almost eight minutes, Miss Burton and her crew have plenty of time to enchant, albeit with that certain moodiness and genuine withdrawal whose omnipresence prevents this piece from ever being perceived as an Easy Listening ditty. Staccato maracas that rattle like venomous snakes, soothing bongo and conga undercurrents, marimba droplets and vibraphone vesicles as well as polyphonic flutes provide a panorama that is of a reduced majesty; the scenery seems to depict a sunrise, but in a non-dramatic way. This remark becomes all the more curious when one realizes that Miriam Burton’s vocals are exactly that: at times willfully over the top, then gloriously united with – and enmeshed in – the deserted steppe.

Part 2 of the suite does not change much in terms of the vocals, but is a more euphonious, upbeat endeavor with punchy drums, Occidental melodies that exude exoticism à la Hollywood and ever-changing rhythm sections that seem more like pearls on a necklace than fully fleshed-out sections. Part 3 closes with a rubicund ambience as evoked by the flute layers and the marimba fusillades, with cautiously laid-back Latin percussion backdrops and enough room to breathe to realize the wideness of the setup. All in all, Rites Of Passage unites the sophisticated structures of symphonies with the carefree attitude of a Jazz sextet, the latter of which absorbs the eclectic paces and transforms them into a soothing concoction. Here, the atmosphere is the most important factor, with the textures coming in second, followed by the melodies and tone sequences.

The six remaining tracks are nowhere as convoluted as Rites Of Passage, but what they lack in oneiric mellowness, they gain in life-affirming glee. Convivial and fast-paced, Miriam Burton rushes through a rotatory reticulation of festive processions, sun-dappled tunes and chain-breaking epiphanies. Kenscoff provides a surprisingly Rock-oriented beat structure that seems like an echopraxia of a choo-chooing train running through the African steppe. The shrill fifes and mildly unnerving la la la vocals provide a distinct counterpart to the gravitas of the opener, with Kalahari Bushmen succeeding with a wonderful drum mélange and half-dangerous syrinx fanfares; the cinematic setup is soon neglected as the cloudy atmosphere makes room for an aural sunburst that comes in the shape of Miss Burton’s prolonged vocals and strong flute-based overtones near the end, thus offering solace and joy.

The five minutes of Congo Lament meanwhile present a delicate quandary. Is it a sad piece or an uplifting one? I call it a saccharified lamento. The vocals are stringently hued in contemplation, with the ligneous marimba blebs being dun-colored and deep, but the dulcet flute bursts and the sweeping maracas push away all too cloudy thoughts yet again. The second section is particularly noteworthy for harboring the Exotica spirit of far-away places, insouciance and enlightenment.

While the comparatively short Yoruba Lady is a remarkably memorable tune not so much due to the echoey afterglow of the drums’ decay but the saltatory vocal range of Miss Burton spanning many a vowel, rising formation and falling cascade, the following Apartheid presents a grave topic and rightfully turns back to a lamenting scenario full of fir-green marimbas, faux-Sicilian guitars, moments of rest in lieu of unrest and that gorgeously maintained scenario of a calm before the storm. There is something in the air, and it is neither frightening nor horribly portentous, making Apartheid an Exotica tune that is worth mentioning due to its – unattractive genre-wise – topic alone. Palm Wine Party is the inebriated closer supercharged with wonkily polylayered marimba superfluids, mountainous flutes, kaleidoscopic Hammond organs, bamboo rods, timbales and congas aplenty as well as histrionic vocals. Texturally speaking, Palm Wine Party offers the greatest granuloma of rich chromaticity, of checkered patterns and varied surfaces without ever feeling gimmicky. A strong and hopeful closer in the tradition of a true Exotica gem.

Vocal Exotica is a hit-or-miss affair, only showing its eupeptic effects in well-distributed doses. Miriam Burton’s African Lament unsurprisingly belongs to this category, but there is an important statement to make in terms of its magic: since it only features wordless – not worthless – vocals, the result is either very tolerable or unwillingly nerve-racking, depending on the attitude and opinion of each listener. I thankfully happen to belong to the former group (it could have been different after all!), and so the occasionally childish and melodramatic but never comical performance of Miriam Burton suits the songs well. There is still one aesthetic factor which prevents even those listeners who are fond of Space-Age gibberish to fully enjoy African Lament, and the crucial point is delivered in its title already: the stylistic gap between sorrowful sequences, no matter how short they be, and the mirthful, gentle look upon an uncertain future.

Miriam Burton and her crew of session musicians tiptoe through the gaps and crevasses that this dichotomy causes, but it is to no avail, no matter how successful Miss Burton is, danger and ambiguity themselves cannot be neglected. If this is of no great importance to you, then by all means fetch the digital-only version released in April 2012 by Smith & Co which is available at a low price. One man’s highlight is another man’s disappointment, so while I am fond of the majestic suite Rites Of Passage, I can easily understand if its shapeshifting gestalt and seemingly arbitrary segues are a bit too labyrinthine and quasi-symphonic to one’s taste. The remaining material, however, is more song-based in the classical sense and offers a great collection of unique Afro-Exotica.

Exotica Review 339: Miriam Burton – African Lament (1961). Originally published on May 10, 2014 at AmbientExotica.com.